Chapter 8 Make Good Decisions

Significant portions of this chapter were adapted from Talya Bauer and Berrin Erdogan’s Organizational Behavior textbook with permission of the authors.

Bauer, T. N., & Erdogan, B. (2010). Organizational Behavior>(Version 1.1). Irvington, NY: Flat World Knowledge.

A peacefulness follows any decision, even the wrong one.

Rita Mae Brown

The hardest thing to learn in life is which bridge to cross and which to burn.

David Russell

Too Many Choices

Andi graduated from Spokane Community College two weeks ago with her degree in Business Management. She is anxious to put her knowledge to good use at a job she enjoys.

Andi has an idea of her perfect job and begins work to apply to those organizations that meet her criteria. Using social media and traditional approaches to job searching, Andi gets three interviews at well-known companies in the Spokane area.

After what seems like a week interviewing, Andi receives two job offers! She is thrilled but isn’t sure which one to choose. One of the offers is for a higher salary than she expected but requires one week of travel per month. The other job is a lower salary and position, but the possibilities to grow with the company seem better. Andi isn’t sure which job to choose.

Big decisions, such as career choices, take a lot of planning and thought to make sure we make the right decision for our needs. This chapter will discuss the ways we can learn to make good personal decisions but also good decisions for the organizations we work for.

8.1 Understanding Decision Making

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

- Define decision making and describe how you can make better decisions.

- Understand the different types of decisions you may make in your career and personal life.

Decision making refers to making choices among alternative courses of action—which may also include inaction. This chapter will help you understand how to make decisions alone or in a group while avoiding common decision-making pitfalls. As you know, the key to positive human relations in these situations is communication and application of emotional intelligence skills such as self-awareness when making decisions alone. Emotional intelligence is required in the form of relationship management when making decisions in groups.

Individuals throughout organizations use the information they gather to make a wide range of decisions. These decisions may affect the lives of others and change the course of an organization. For example, the decisions made by executives and consulting firms for Enron ultimately resulted in a $60 billion loss for investors, thousands of employees without jobs, and the loss of all employee retirement funds. But Sherron Watkins, a former Enron employee and now-famous whistleblower, uncovered the accounting problems and tried to enact change. Similarly, the decision made by firms to trade in mortgage-backed securities is having negative consequences for the entire economy in the United States. All parties involved in such outcomes made a decision, and everyone is now living with the consequences of those decisions.

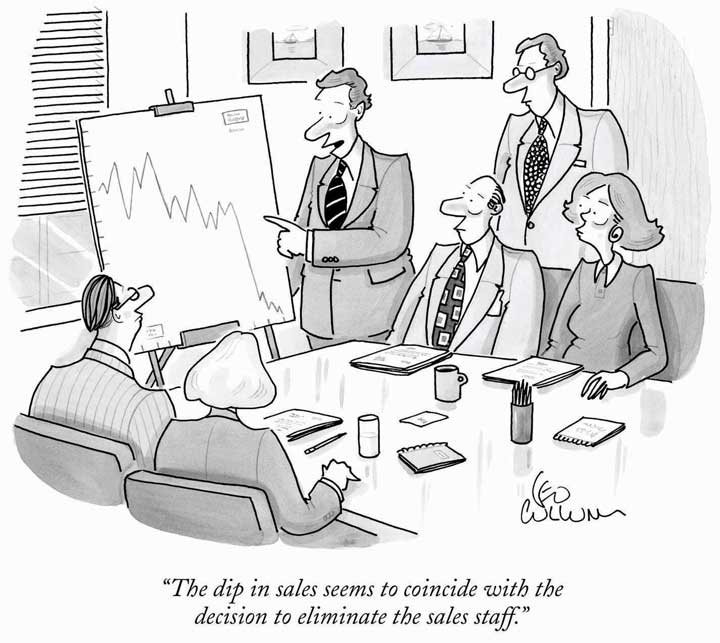

Figure 8.1

It is important to remember that decisions have consequences.

© The New Yorker Collection. 2002. Leo Cullum from cartoonbank.com. All rights reserved.

Types of Decisions

Despite the far-reaching nature of the decisions in the previous example, not all decisions have major consequences or even require a lot of thought. For example, before you come to class, you make simple and habitual decisions such as what to wear, what to eat, and which route to take as you go to and from home and school. You probably do not spend much time on these mundane decisions. These types of straightforward decisions are termed programmed decisions, or decisions that occur frequently enough that we develop an automated response to them. The automated response we use to make these decisions is called the decision rule. For example, many restaurants face customer complaints as a routine part of doing business. Because complaints are a recurring problem, responding to them may become a programmed decision. The restaurant might enact a policy stating that every time they receive a valid customer complaint, the customer should receive a free dessert, which represents a decision rule.

On the other hand, unique and important decisions require conscious thinking, information gathering, and careful consideration of alternatives. These are called nonprogrammed decisions. For example, in 2005 McDonald’s Corporation became aware of the need to respond to growing customer concerns regarding the unhealthy aspects (high in fat and calories) of the food they sell. This is a nonprogrammed decision, because for several decades, customers of fast-food restaurants were more concerned with the taste and price of the food rather than its healthiness. In response to this problem, McDonald’s decided to offer healthier alternatives such as the choice to substitute French fries in Happy Meals with apple slices, and in 2007 they banned the use of trans fat at their restaurants.

Figure 8.2

In order to ensure consistency around the globe such as at this St. Petersburg, Russia, location, McDonald’s Corporation trains all restaurant managers at Hamburger University, where they take the equivalent of two years of college courses and learn how to make decisions on the job. The curriculum is taught in twenty-eight languages.

A crisis situation also constitutes a nonprogrammed decision for companies. For example, the leadership of Nutrorim was facing a tough decision. They had recently introduced a new product, ChargeUp with Lipitrene, an improved version of their popular sports drink powder, ChargeUp. At some point, a phone call came from a state health department to inform them of eleven cases of gastrointestinal distress that might be related to their product, which led to a decision to recall ChargeUp. The decision was made without an investigation of the information. While this decision was conservative, it was made without a process that weighed the information. Two weeks later it became clear that the reported health problems were unrelated to Nutrorim’s product. In fact, all the cases were traced back to a contaminated health club juice bar. However, the damage to the brand and to the balance sheets was already done. This unfortunate decision caused Nutrorim to rethink the way decisions were made when under pressure. The company now gathers information to make informed choices even when time is of the essence.Garvin, D. A. (2006, January). All the wrong moves. Harvard Business Review, 84, 18–23.

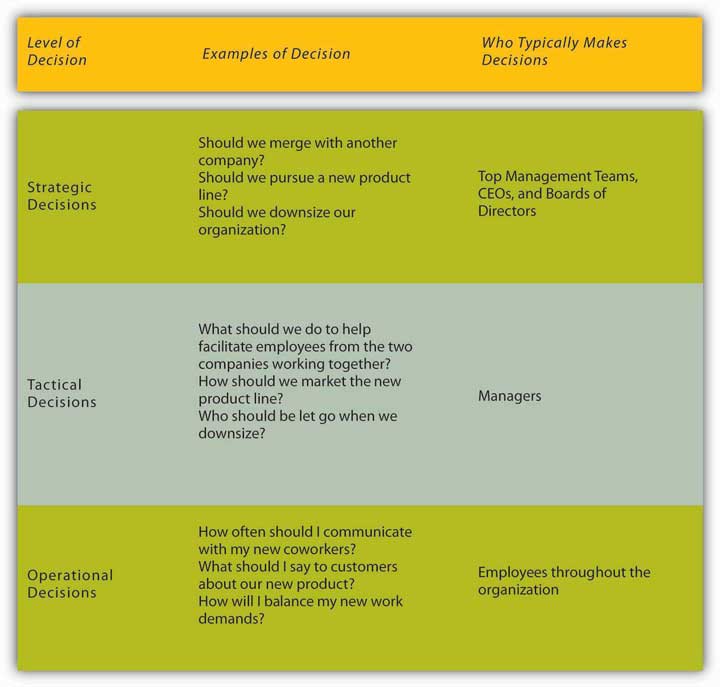

Decisions can be classified into three categories based on the level at which they occur. Strategic decisions set the course of an organization. Tactical decisions are decisions about how things will get done. Finally, operational decisions refer to decisions that employees make each day to make the organization run. For example, think about the restaurant that routinely offers a free dessert when a customer complaint is received. The owner of the restaurant made a strategic decision to have great customer service. The manager of the restaurant implemented the free dessert policy as a way to handle customer complaints, which is a tactical decision. Finally, the servers at the restaurant are making individual decisions each day by evaluating whether each customer complaint received is legitimate and warrants a free dessert.

Figure 8.3 Examples of Decisions Commonly Made within Organizations

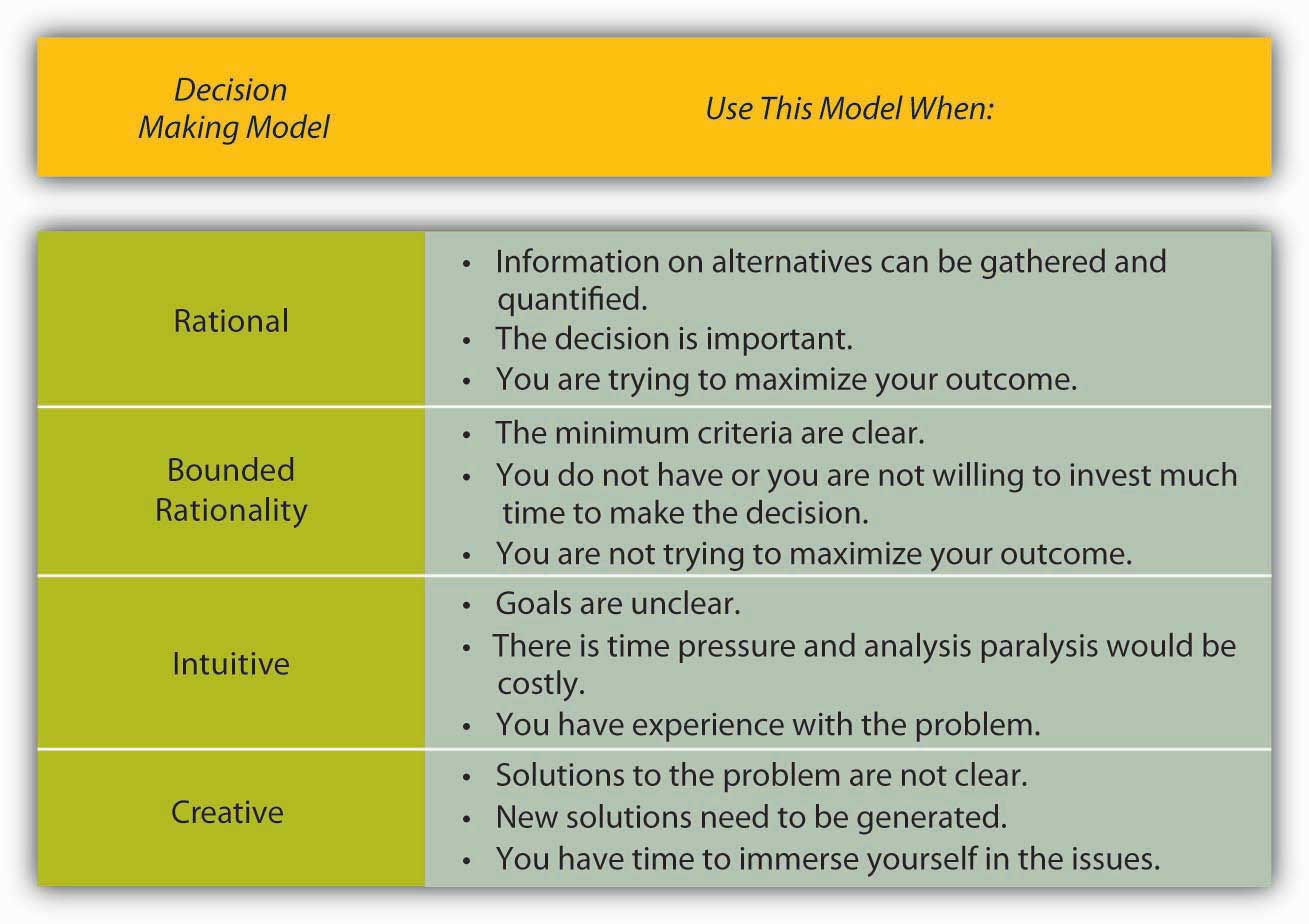

In this chapter we are going to discuss different decision-making models designed to understand and evaluate the effectiveness of nonprogrammed decisions. We will cover four decision-making approaches, starting with the rational decision-making model, moving to the bounded rationality decision-making model, the intuitive decision-making model, and ending with the creative decision-making model. The importance of making good decisions relates to our ability to manage our emotional intelligence to make sure we make the right decisions. These models will help us make better decisions, which results in better human relations.

Making Rational Decisions

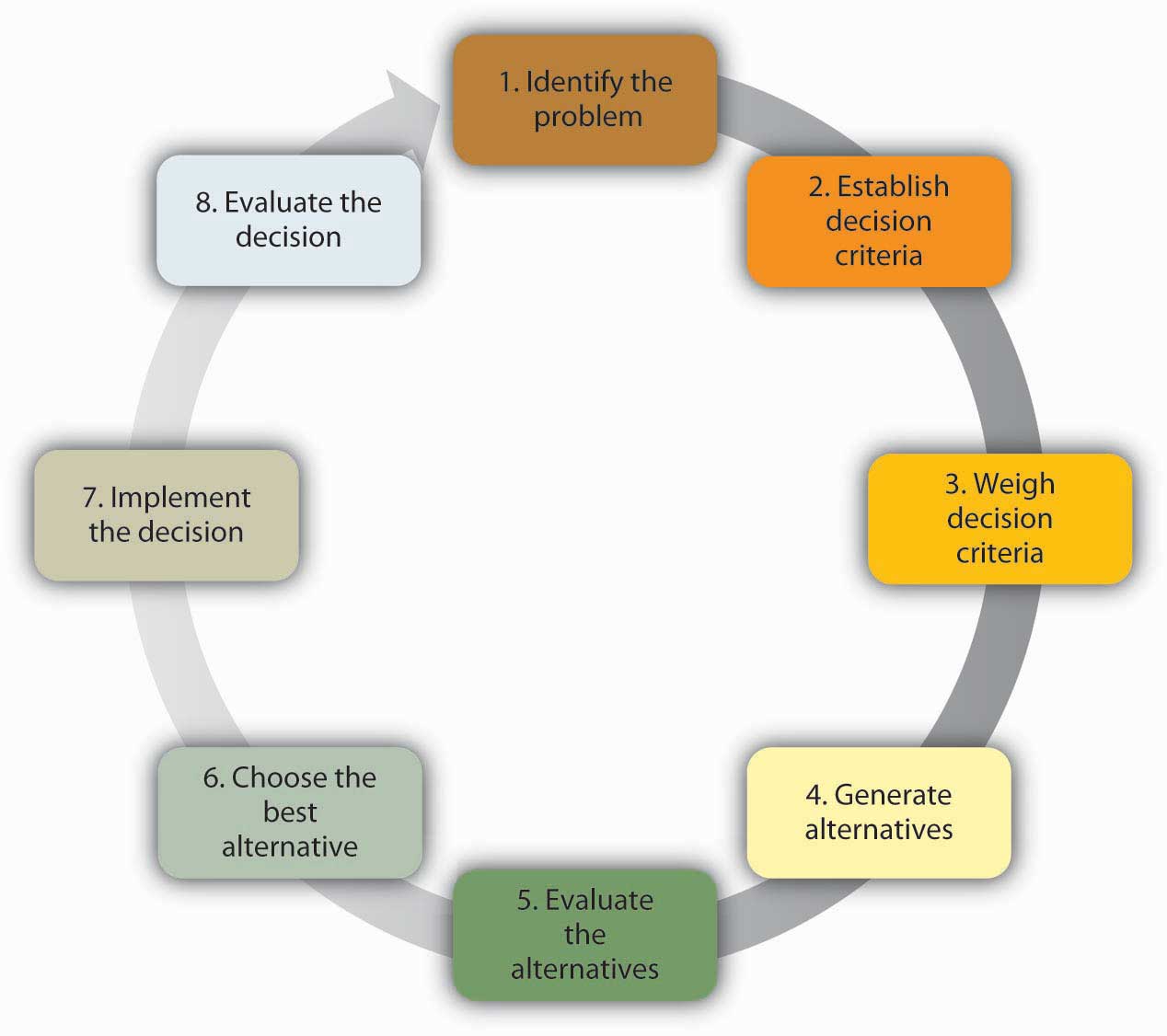

The rational decision-making model describes a series of steps that decision makers should consider if their goal is to maximize the quality of their outcomes. In other words, if you want to make sure that you make the best choice, going through the formal steps of the rational decision-making model may make sense.

Let’s imagine that your old, clunky car has broken down, and you have enough money saved for a substantial down payment on a new car. It will be the first major purchase of your life, and you want to make the right choice. The first step, therefore, has already been completed—we know that you want to buy a new car. Next, in step 2, you’ll need to decide which factors are important to you. How many passengers do you want to accommodate? How important is fuel economy to you? Is safety a major concern? You only have a certain amount of money saved, and you don’t want to take on too much debt, so price range is an important factor as well. If you know you want to have room for at least five adults, get at least twenty miles per gallon, drive a car with a strong safety rating, not spend more than $22,000 on the purchase, and like how it looks, you have identified the decision criteria. All the potential options for purchasing your car will be evaluated against these criteria. Before we can move too much further, you need to decide how important each factor is to your decision in step 3. If each is equally important, then there is no need to weigh them, but if you know that price and mpg are key factors, you might weigh them heavily and keep the other criteria with medium importance. Step 4 requires you to generate all alternatives about your options. Then, in step 5, you need to use this information to evaluate each alternative against the criteria you have established. You choose the best alternative (step 6), and then you would go out and buy your new car (step 7).

Of course, the outcome of this decision will influence the next decision made. That is where step 8 comes in. For example, if you purchase a car and have nothing but problems with it, you will be less likely to consider the same make and model when purchasing a car the next time.

Figure 8.4 Steps in the Rational Decision-Making Model

While decision makers can get off track during any of these steps, research shows that searching for alternatives in the fourth step can be the most challenging and often leads to failure. In fact, one researcher found that no alternative generation occurred in 85 percent of the decisions he studied.Nutt, P. C. (1994). Types of organizational decision processes. Administrative Science Quarterly, 29, 414–550. Conversely, successful managers know what they want at the outset of the decision-making process, set objectives for others to respond to, carry out an unrestricted search for solutions, get key people to participate, and avoid using their power to push their perspective.Nutt, P. C. (1998). Surprising but true: Half the decisions in organizations fail. Academy of Management Executive, 13, 75–90.

The rational decision-making model has important lessons for decision makers. First, when making a decision, you may want to make sure that you establish your decision criteria before you search for alternatives. This would prevent you from liking one option too much and setting your criteria accordingly. For example, let’s say you started browsing cars online before you generated your decision criteria. You may come across a car that you feel reflects your sense of style and you develop an emotional bond with the car. Then, because of your love for the particular car, you may say to yourself that the fuel economy of the car and the innovative braking system are the most important criteria. After purchasing it, you may realize that the car is too small for your friends to ride in the back seat, which was something you should have thought about. Setting criteria before you search for alternatives may prevent you from making such mistakes. Another advantage of the rational model is that it urges decision makers to generate all alternatives instead of only a few. By generating a large number of alternatives that cover a wide range of possibilities, you are unlikely to make a more effective decision that does not require sacrificing one criterion for the sake of another.

Despite all its benefits, you may have noticed that this decision-making model involves a number of unrealistic assumptions as well. It assumes that people completely understand the decision to be made, that they know all their available choices, that they have no perceptual biases, and that they want to make optimal decisions. Nobel Prize–winning economist Herbert Simon observed that while the rational decision-making model may be a helpful device in aiding decision makers when working through problems, it doesn’t represent how decisions are frequently made within organizations. In fact, Simon argued that it didn’t even come close.

Think about how you make important decisions in your life. It is likely that you rarely sit down and complete all eight of the steps in the rational decision-making model. For example, this model proposed that we should search for all possible alternatives before making a decision, but that process is time consuming, and individuals are often under time pressure to make decisions. Moreover, even if we had access to all the information that was available, it could be challenging to compare the pros and cons of each alternative and rank them according to our preferences. Anyone who has recently purchased a new laptop computer or cell phone can attest to the challenge of sorting through the different strengths and limitations of each brand and model and arriving at the solution that best meets particular needs. In fact, the availability of too much information can lead to analysis paralysis, in which more and more time is spent on gathering information and thinking about it, but no decisions actually get made. A senior executive at Hewlett-Packard Development Company LP admits that his company suffered from this spiral of analyzing things for too long to the point where data gathering led to “not making decisions, instead of us making decisions.”Zell, D. M., Glassman, A. M., & Duron, S. A. (2007). Strategic management in turbulent times: The short and glorious history of accelerated decision making at Hewlett-Packard. Organizational Dynamics, 36, 93–104. Moreover, you may not always be interested in reaching an optimal decision. For example, if you are looking to purchase a house, you may be willing and able to invest a great deal of time and energy to find your dream house, but if you are only looking for an apartment to rent for the academic year, you may be willing to take the first one that meets your criteria of being clean, close to campus, and within your price range.

Making “Good Enough” Decisions

The bounded rationality model of decision making recognizes the limitations of our decision-making processes. According to this model, individuals knowingly limit their options to a manageable set and choose the first acceptable alternative without conducting an exhaustive search for alternatives. An important part of the bounded rationality approach is the tendency to satisfice (a term coined by Herbert Simon from satisfy and suffice), which refers to accepting the first alternative that meets your minimum criteria. For example, many college graduates do not conduct a national or international search for potential job openings. Instead, they focus their search on a limited geographic area, and they tend to accept the first offer in their chosen area, even if it may not be the ideal job situation. Satisficing is similar to rational decision making. The main difference is that rather than choosing the best option and maximizing the potential outcome, the decision maker saves cognitive time and effort by accepting the first alternative that meets the minimum threshold.

Making Intuitive Decisions

The intuitive decision-making model has emerged as an alternative to other decision making processes. This model refers to arriving at decisions without conscious reasoning. A total of 89 percent of managers surveyed admitted to using intuition to make decisions at least sometimes and 59 percent said they used intuition often.Burke, L. A., & Miller, M. K. (1999). Taking the mystery out of intuitive decision making. Academy of Management Executive, 13, 91–98. Managers make decisions under challenging circumstances, including time pressures, constraints, a great deal of uncertainty, changing conditions, and highly visible and high-stakes outcomes. Thus, it makes sense that they would not have the time to use the rational decision-making model. Yet when CEOs, financial analysts, and health care workers are asked about the critical decisions they make, seldom do they attribute success to luck. To an outside observer, it may seem like they are making guesses as to the course of action to take, but it turns out that experts systematically make decisions using a different model than was earlier suspected. Research on life-or-death decisions made by fire chiefs, pilots, and nurses finds that experts do not choose among a list of well thought out alternatives. They don’t decide between two or three options and choose the best one. Instead, they consider only one option at a time. The intuitive decision-making model argues that in a given situation, experts making decisions scan the environment for cues to recognize patterns.Breen, B. (2000, August). What’s your intuition? Fast Company, 290; Klein, G. (2003). Intuition at work. New York: Doubleday; Salas, E., & Klein, G. (2001). Linking expertise and naturalistic decision making. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Once a pattern is recognized, they can play a potential course of action through to its outcome based on their prior experience. Thanks to training, experience, and knowledge, these decision makers have an idea of how well a given solution may work. If they run through the mental model and find that the solution will not work, they alter the solution before setting it into action. If it still is not deemed a workable solution, it is discarded as an option, and a new idea is tested until a workable solution is found. Once a viable course of action is identified, the decision maker puts the solution into motion. The key point is that only one choice is considered at a time. Novices are not able to make effective decisions this way, because they do not have enough prior experience to draw upon.

Making Creative Decisions

In addition to the rational decision making, bounded rationality, and intuitive decision-making models, creative decision making is a vital part of being an effective decision maker. Creativity is the generation of new, imaginative ideas. With the flattening of organizations and intense competition among companies, individuals and organizations are driven to be creative in decisions ranging from cutting costs to generating new ways of doing business. Please note that, while creativity is the first step in the innovation process, creativity and innovation are not the same thing. Innovation begins with creative ideas, but it also involves realistic planning and follow-through. Innovations such as 3M’s Clearview Window Tinting grow out of a creative decision-making process about what may or may not work to solve real-world problems.

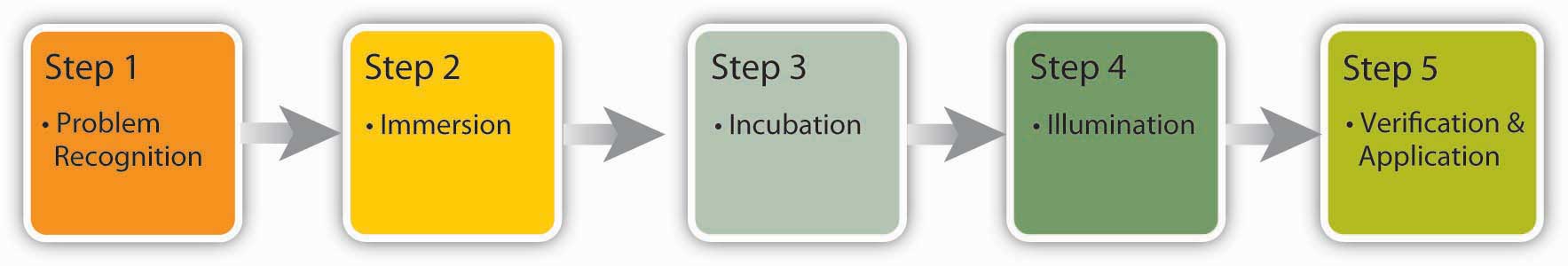

The five steps to creative decision making are similar to the previous decision-making models in some keys ways. All the models include problem identification, which is the step in which the need for problem solving becomes apparent. If you do not recognize that you have a problem, it is impossible to solve it. Immersion is the step in which the decision maker consciously thinks about the problem and gathers information. A key to success in creative decision making is having or acquiring expertise in the area being studied. Then, incubation occurs. During incubation, the individual sets the problem aside and does not think about it for a while. At this time, the brain is actually working on the problem unconsciously. Then comes illumination, or the insight moment when the solution to the problem becomes apparent to the person, sometimes when it is least expected. This sudden insight is the “eureka” moment, similar to what happened to the ancient Greek inventor Archimedes, who found a solution to the problem he was working on while taking a bath. Finally, the verification and application stage happens when the decision maker consciously verifies the feasibility of the solution and implements the decision.

Figure 8.5 The Creative Decision-Making Process

A NASA scientist describes his decision-making process leading to a creative outcome as follows: He had been trying to figure out a better way to de-ice planes to make the process faster and safer. After recognizing the problem, he immersed himself in the literature to understand all the options, and he worked on the problem for months trying to figure out a solution. It was not until he was sitting outside a McDonald’s restaurant with his grandchildren that it dawned on him. The golden arches of the M of the McDonald’s logo inspired his solution—he would design the de-icer as a series of Ms.Interview conducted by author Talya Bauer at Ames Research Center, Mountain View, CA, 1990.This represented the illumination stage. After he tested and verified his creative solution, he was done with that problem, except to reflect on the outcome and process.

How Do You Know If Your Decision-Making Process Is Creative?

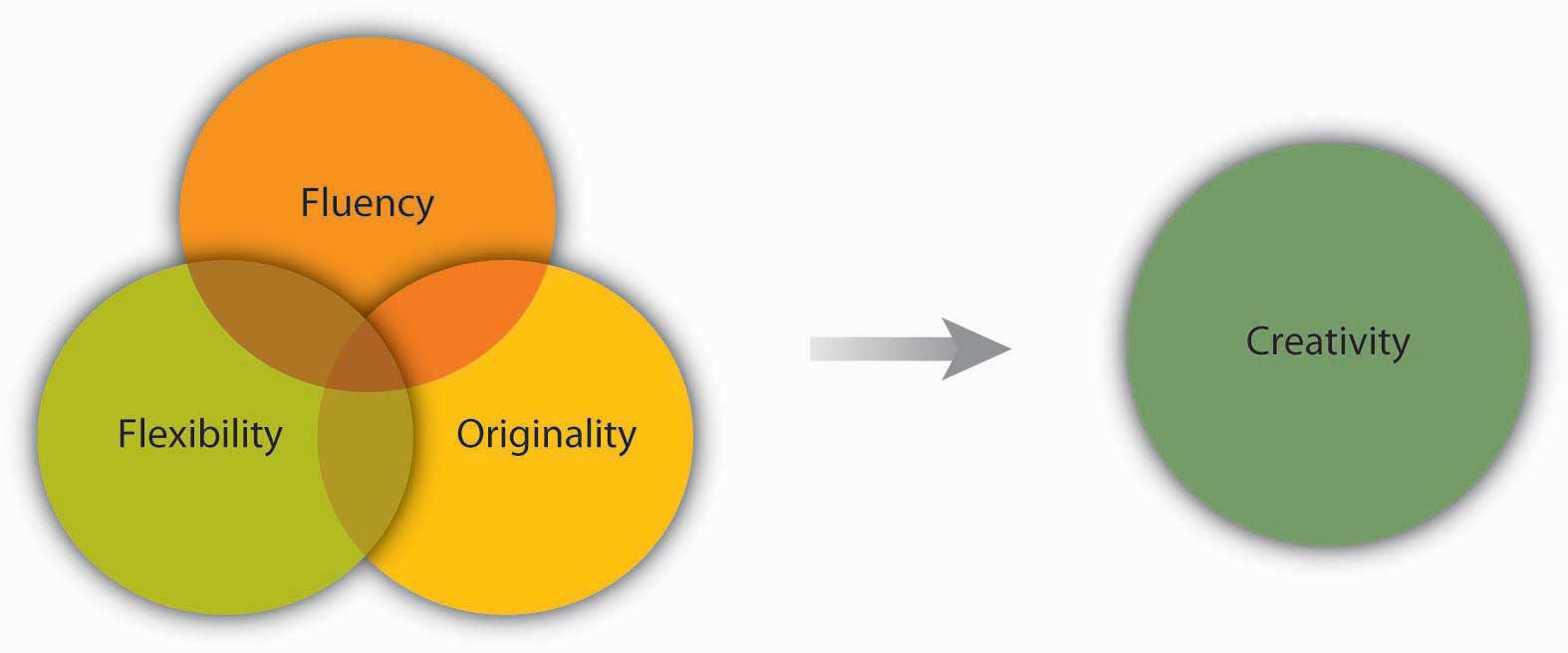

Researchers focus on three factors to evaluate the level of creativity in the decision-making process. Fluency refers to the number of ideas a person is able to generate. Flexibility refers to how different the ideas are from one another. If you are able to generate several distinct solutions to a problem, your decision-making process is high on flexibility. Originality refers to how unique a person’s ideas are. You might say that Reed Hastings, founder and CEO of Netflix Inc., is a pretty creative person. His decision-making process shows at least two elements of creativity. We do not know exactly how many ideas he had over the course of his career, but his ideas are fairly different from each other. After teaching math in Africa with the Peace Corps, Hastings was accepted at Stanford, where he earned a master’s degree in computer science. Soon after starting work at a software company, he invented a successful debugging tool, which led to his founding of the computer troubleshooting company Pure Software LLC in 1991. After a merger and the subsequent sale of the resulting company in 1997, Hastings founded Netflix, which revolutionized the DVD rental business with online rentals delivered through the mail with no late fees. In 2007, Hastings was elected to Microsoft’s board of directors. As you can see, his ideas are high in originality and flexibility.Conlin, M. (2007, September 14). Netflix: Recruiting and retaining the best talent. Business Week Online. Retrieved March 1, 2008, from http://www.businessweek.com/stories/2007-09-13/netflix-recruiting-and-retaining-the-best-talentbusinessweek -business-news-stock-market-and-financial-advice.

Figure 8.6 Dimensions of Creativity

Some experts have proposed that creativity occurs as an interaction among three factors: people’s personality traits (openness to experience, risk taking), their attributes (expertise, imagination, motivation), and the situational context (encouragement from others, time pressure, physical structures).Amabile, T. M. (1988). A model of creativity and innovation in organizations. In B. M. Staw & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior, (vol. 10, pp. 123–67). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press; Amabile, T. M., Conti, R., Coon, H., Lazenby, J., & Herron, M. (1996). Assessing the work environment for creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 39, 1154–84; Ford, C. M., & Gioia, D. A. (2000). Factors influencing creativity in the domain of managerial decision making. Journal of Management, 26, 705–32; Tierney, P., Farmer, S. M., & Graen, G. B. (1999). An examination of leadership and employee creativity: The relevance of traits and relationships. Personnel Psychology, 52, 591–620; Woodman, R. W., Sawyer, J. E., & Griffin, R. W. (1993). Toward a theory of organizational creativity. Academy of Management Review, 18, 293–321. For example, research shows that individuals who are open to experience, less conscientious, more self-accepting, and more impulsive tend to be more creative.Feist, G. J. (1998). A meta-analysis of personality in scientific and artistic creativity. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 2, 290–309.

Ideas for Enhancing Creativity in Groups

Team Composition

- Diversify your team to give them more inputs to build on and more opportunities to create functional conflict while avoiding personal conflict.

- Change group membership to stimulate new ideas and new interaction patterns.

- Leaderless teams can allow teams freedom to create without trying to please anyone up front.

Team Process

- Engage in brainstorming to generate ideas. Remember to set a high goal for the number of ideas the group should come up with, encourage wild ideas, and take brainwriting breaks.

- Use the nominal group technique (see Tools and Techniques for Making Better Decisions below) in person or electronically to avoid some common group process pitfalls. Consider anonymous feedback as well.

- Use analogies to envision problems and solutions.

Leadership

- Challenge teams so that they are engaged but not overwhelmed.

- Let people decide how to achieve goals rather than telling them what goals to achieve.

- Support and celebrate creativity even when it leads to a mistake. Be sure to set up processes to learn from mistakes as well.

- Role model creative behavior.

Culture

- Institute organizational memory so that individuals do not spend time on routine tasks.

- Build a physical space conducive to creativity that is playful and humorous—this is a place where ideas can thrive.

- Incorporate creative behavior into the performance appraisal process.

Sources: Adapted from ideas in Amabile, T. M. (1998). How to kill creativity. Harvard Business Review, 76, 76–87; Gundry, L. K., Kickul, J. R., & Prather, C. W. (1994). Building the creative organization. Organizational Dynamics, 22, 22–37; Keith, N., & Frese, M. (2008). Effectiveness of error management training: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 59–69. Pearsall, M. J., Ellis, A. P. J., & Evans, J. M. (2008). Unlocking the effects of gender faultlines on team creativity: Is activation the key? Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 225–34. Thompson, L. (2003). Improving the creativity of organizational work groups. Academy of Management Executive, 17, 96–109.

There are many techniques available that enhance and improve creativity. Linus Pauling, the Nobel Prize winner who popularized the idea that vitamin C could help strengthen the immune system, said, “The best way to have a good idea is to have a lot of ideas.”Quote retrieved May 1, 2008, from http://www.whatquote.com/quotes/linus-pauling/250801-the-best-way-to-have.htm. One popular method of generating ideas is to use brainstorming. Brainstorming is a group process of generating ideas that follow a set of guidelines, including no criticism of ideas during the brainstorming process, the idea that no suggestion is too crazy, and building on other ideas (piggybacking). Research shows that the quantity of ideas actually leads to better idea quality in the end, so setting high idea quotas, in which the group must reach a set number of ideas before they are done, is recommended to avoid process loss and maximize the effectiveness of brainstorming. Another unique aspect of brainstorming is that since the variety of backgrounds and approaches give the group more to draw upon, the more people are included in the process, the better the decision outcome will be. A variation of brainstorming is wildstorming, in which the group focuses on ideas that are impossible and then imagines what would need to happen to make them possible.Scott, G., Leritz, L. E., & Mumford, M. D. (2004). The effectiveness of creativity training: A quantitative review. Creativity Research Journal, 16, 361–88.

One example of a creative decision making model is the Edward Debono model. The Edward Debono’s model of the Six Thinking Hats provides us with a different way of thinking about the way we make decisions. The six hats provide us with perspectives from six different perspectives. Similar to the rational decision making model discussed earlier, this model uses hats to represent the steps we need to follow in order to make good decisions. For example, the white hat helps us look at the facts of the situation. The red hat helps us look at the emotional aspect of the problem or solution. The black hat helps us to look at the negatives of the solution, while the yellow hat helps us think about the positives of the solution. The green hat allows us to come up with potential solutions or courses of action, while the blue hat helps us manage the process of making the decision. For example, consider the opening scenario where Andi is considering which job to accept. If she were using the six hats model, first she would look at the facts—that is, the aspects of each job offer (white hat). Then, she would look at how she feel (red hat) about each job. Next, she would look at the downsides of each job (black hat). Then, she would look at the positives of each job (yellow hat). Next, she would use the green hat to look at the job offers from a creative way and look at potential of choosing one job over another. Finally, the blue hat would cause Andi to make sure she used all hats to make a decision and, based on the data, would go ahead and make the best choice.

Figure 8.7

Which decision-making model should I use?

Why Human Relations?

Sometimes when we are faced with making a hard decision, we can be overly emotional and therefore make the wrong one. By developing self-awareness skills (I am feeling xx way) and then managing our emotions once we recognize them, we can learn to make healthy, wise decisions. As you read about the Debono decision-making model, this model specifically asks that you look at your own emotions and the emotions of others. This is part of self-awareness and social awareness in emotional intelligence. Without these skills, it can be difficult to make good decisions.

The ability to make good decisions can help us become happier people, thus better at human relations. When we understand how we feel about a certain decision we have to make, we can look realistically at all possible solutions from a cognitive level, which allows us to also make better decisions. These emotional intelligence skills, specifically self-awareness and self-management, can help us make thoughtful, sound decisions that improve our productivity, happiness, and satisfaction. All these skills are important ingredients to positive human relations at work and in our personal lives.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Decision making is choosing among alternative courses of action, including inaction.

- There are different types of decisions ranging from automatic, programmed decisions to more intensive nonprogrammed decisions.

- Structured decision-making processes include rational, bounded rationality, intuitive, and creative decision making.

- Each of these can be useful, depending on the circumstances and the problem that needs to be solved.

EXERCISES

- What do you see as the main difference between a successful and an unsuccessful decision? How much does luck versus skill have to do with it? How much time needs to pass to know if a decision is successful or not?

- Research has shown that over half of the decisions made within organizations fail. Does this surprise you? Why or why not?

- Have you used the rational decision-making model to make a decision? What was the context? How well did the model work?

- Share an example of a decision in which you used satisficing. Were you happy with the outcome? Why or why not? When would you be most likely to engage in satisficing?

- Do you think intuition is respected as a decision-making style? Do you think it should be? Why or why not?

8.2 Faulty Decision Making

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

- Understand overconfidence bias and how to avoid it.

- Understand hindsight, anchoring, and framing bias and how to avoid them.

- Understand escalation of commitment and how to avoid it.

Avoiding Decision-Making Traps

No matter which model you use, it is important to know and avoid the decision-making traps that exist. Daniel Kahnemann (another Nobel Prize winner) and Amos Tversky spent decades studying how people make decisions. They found that individuals are influenced by overconfidence bias, hindsight bias, anchoring bias, framing bias, and escalation of commitment. An awareness of some of the pitfalls of decision making enhances our ability to make good decisions. When we make good decisions, we are happier, which makes for more positive human relations skills.

Figure 8.8

Source: Short, J., Bauer, T. N., Simon, L., & Ketchen, D. (2009). Atlas Black, managing to succeed. New York: Flat World Knowledge. Reprinted by permission.

Overconfidence bias occurs when individuals overestimate their ability to predict future events. Many people exhibit signs of overconfidence. For example, 82 percent of the drivers surveyed feel they are in the top 30 percent of safe drivers, 86 percent of students at the Harvard Business School say they are better looking than their peers, and doctors consistently overestimate their ability to detect problems.Tilson, W. (1999, September 20). The perils of investor overconfidence. Retrieved March 1, 2008, from http://www.fool.com/BoringPort/1999/BoringPort990920.htm. Much like friends that are 100 percent sure they can pick the winners of this week’s football games despite evidence to the contrary, these individuals are suffering from overconfidence bias. Similarly, in 2008, the French bank Société Générale lost over $7 billion as a result of the rogue actions of a single trader. Jérôme Kerviel, a junior trader in the bank, had extensive knowledge of the bank’s control mechanisms and used this knowledge to beat the system. Interestingly, he did not make any money from these transactions himself, and his sole motive was to be successful. He secretly started making risky moves while hiding the evidence. He made a lot of profit for the company early on and became overly confident in his abilities to make even more. In his defense, he was merely able to say that he got “carried away.”The rogue rebuttal. (2008, February 9). Economist, 386, 82. People who purchase lottery tickets as a way to make money are probably suffering from overconfidence bias. It is three times more likely for a person driving ten miles to buy a lottery ticket to be killed in a car accident than to win the jackpot.Orkin, M. (1991). Can you win? The real odds for casino gambling, sports betting and lotteries. New York: W. H. Freeman. Further, research shows that overconfidence leads to less successful negotiations.Neale, M. A., & Bazerman, M. H. (1985). The effects of framing and negotiator overconfidence on bargaining behaviors and outcomes. Academy of Management Journal, 28, 34–49. To avoid this bias, take the time to stop and ask yourself if you are being realistic in your judgments.

Hindsight bias is the opposite of overconfidence bias, as it occurs when looking backward in time and mistakes seem obvious after they have already occurred. In other words, after a surprising event occurred, many individuals are likely to think that they already knew the event was going to happen. This bias may occur because they are selectively reconstructing the events. Hindsight bias tends to become a problem when judging someone else’s decisions. For example, let’s say a company driver hears the engine making unusual sounds before starting the morning routine. Being familiar with this car in particular, the driver may conclude that the probability of a serious problem is small and continues to drive the car. During the day, the car malfunctions and stops miles away from the office. It would be easy to criticize the decision to continue to drive the car because in hindsight, the noises heard in the morning would make us believe that the driver should have known something was wrong and taken the car in for service. However, the driver in question may have heard similar sounds before with no consequences, so based on the information available at the time, continuing with the regular routine may have been a reasonable choice. Therefore, it is important for decision makers to remember this bias before passing judgments on other people’s actions.

Anchoring refers to the tendency for individuals to rely too heavily on a single piece of information. Job seekers often fall into this trap by focusing on a desired salary while ignoring other aspects of the job offer such as additional benefits, fit with the job, and working environment. Similarly but more dramatically, lives were lost in the Great Bear Wilderness Disaster when the coroner, within five minutes of arriving at the accident scene, declared all five passengers of a small plane dead, which halted the search effort for potential survivors. The next day two survivors who had been declared dead walked out of the forest. How could a mistake like this have been made? One theory is that decision biases played a large role in this serious error, and anchoring on the fact that the plane had been consumed by flames led the coroner to call off the search for any possible survivors.Becker, W. S. (2007). Missed opportunities: The Great Bear Wilderness Disaster. Organizational Dynamics, 36, 363–76.

Framing bias is another concern for decision makers. Framing bias refers to the tendency of decision makers to be influenced by the way that a situation or problem is presented. For example, when making a purchase, customers find it easier to let go of a discount as opposed to accepting a surcharge, even though they both might cost the person the same amount of money. Similarly, customers tend to prefer a statement such as “85 percent lean beef” as opposed to “15 percent fat.”Li, S., Sun, Y., & Wang, Y. (2007). 50% off or buy one get one free? Frame preference as a function of consumable nature in dairy products. Journal of Social Psychology, 147, 413–21. It is important to be aware of this tendency, because depending on how a problem is presented to us, we might choose an alternative that is disadvantageous simply because of the way it is framed.

Escalation of commitment occurs when individuals continue on a failing course of action after information reveals it may be a poor path to follow. It is sometimes called the “sunken costs fallacy,” because continuation is often based on the idea that one has already invested in the course of action. For example, imagine a person who purchases a used car, which turns out to need something repaired every few weeks. An effective way of dealing with this situation might be to sell the car without incurring further losses, donate the car, or use it until it falls apart. However, many people would spend hours of their time and hundreds, even thousands of dollars repairing the car in the hopes that they might recover their initial investment. Thus, rather than cutting their losses, they waste time and energy while trying to justify their purchase of the car.

A classic example of escalation of commitment from the corporate world is Motorola Inc.’s Iridium project. In the 1980s, phone coverage around the world was weak. For example, it could take hours of dealing with a chain of telephone operators in several different countries to get a call through from Cleveland to Calcutta. There was a real need within the business community to improve phone access around the world. Motorola envisioned solving this problem using sixty-six low-orbiting satellites, enabling users to place a direct call to any location around the world. At the time of idea development, the project was technologically advanced, sophisticated, and made financial sense. Motorola spun off Iridium as a separate company in 1991. It took researchers a total of fifteen years to develop the product from idea to market release. However, in the 1990s, the landscape for cell phone technology was dramatically different from that in the 1980s, and the widespread cell phone coverage around the world eliminated most of the projected customer base for Iridium. Had they been paying attention to these developments, the decision makers could have abandoned the project at some point in the early 1990s. Instead, they released the Iridium phone to the market in 1998. The phone cost $3,000, and it was literally the size of a brick. Moreover, it was not possible to use the phone in moving cars or inside buildings. Not surprisingly, the launch was a failure, and Iridium filed for bankruptcy in 1999.Finkelstein, S., & Sanford, S. H. (2000, November). Learning from corporate mistakes: The rise and fall of Iridium. Organizational Dynamics, 29(2), 138–48. In the end, the company was purchased for $25 million by a group of investors (whereas it cost the company $5 billion to develop its product), scaled down its operations, and modified it for use by the Department of Defense to connect soldiers in remote areas not served by land lines or cell phones.

Figure 8.9

Motorola released the Iridium phone to the market in 1998. The phone cost $3,000 and it was literally the size of a brick.

Why does escalation of commitment occur? There may be many reasons, but two are particularly important. First, decision makers may not want to admit that they were wrong. This may be because of personal pride or being afraid of the consequences of such an admission. Second, decision makers may incorrectly believe that spending more time and energy might somehow help them recover their losses. Effective decision makers avoid escalation of commitment by distinguishing between when persistence may actually pay off versus when it might mean escalation of commitment. To avoid escalation of commitment, you might consider having strict turning back points. For example, you might determine up front that you will not spend more than $500 trying to repair the car and will sell it when you reach that point. You might also consider assigning separate decision makers for the initial buying and subsequent selling decisions. Periodic evaluations of an initially sound decision to see whether the decision still makes sense is also another way of preventing escalation of commitment. This type of review becomes particularly important in projects such as the Iridium phone, in which the initial decision is not immediately implemented but instead needs to go through a lengthy development process. In such cases, it becomes important to periodically assess the soundness of the initial decision in the face of changing market conditions. Finally, creating an organizational climate in which individuals do not fear admitting that their initial decision no longer makes economic sense would go a long way in preventing escalation of commitment, as it could lower the regret the decision maker may experience.Wong, K. F. E., & Kwong, J. Y. Y. (2007). The role of anticipated regret in escalation of commitment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 545–54.

So far we have focused on how individuals make decisions and how to avoid decision traps. Next we shift our focus to the group level. There are many similarities as well as many differences between individual and group decision making. There are many factors that influence group dynamics and also affect the group decision-making process. We will discuss some of them in the following section.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Understanding decision-making traps can help you avoid and manage them.

- Overconfidence bias can cause you to ignore obvious information.

- Hindsight bias can similarly cause a person to incorrectly believe in the ability to predict events.

- Anchoring and framing biases show the importance of the way problems or alternatives are presented in influencing one’s decision.

- Escalation of commitment demonstrates how individuals’ desire to be consistent or avoid admitting a mistake can cause them to continue to invest in a decision that is no longer prudent.

EXERCISES

- Describe a time when you fell into one of the decision-making traps. How did you come to realize that you had made a poor decision?

- How can you avoid escalation of commitment?

- Share an example of anchoring.

- Which of the traps seems the most dangerous for decision makers and why?

8.3 Decision Making in Groups

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

- Understand the pros and cons of individual and group decisions you will make in your career.

- Learn to recognize the signs of groupthink and determine if it is happening to your workgroup.

- Be able to recognize and use a variety of tools in your decision-making processes.

When It Comes to Decision Making, Are Two Heads Better Than One?

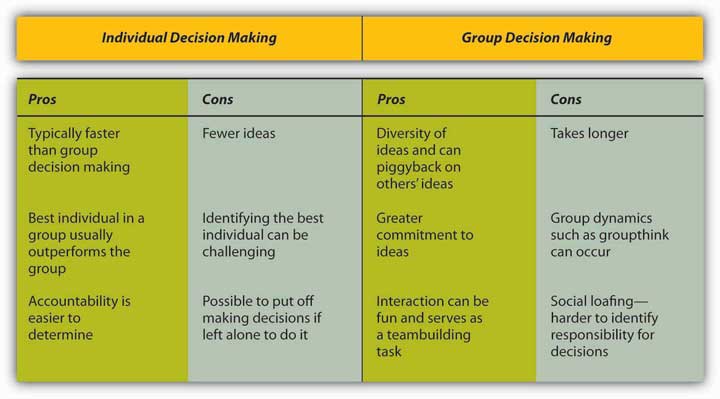

The answer to this question depends on several factors. Group decision making has the advantage of drawing from the experiences and perspectives of a larger number of individuals. Hence, a group may have the potential to be more creative and lead to more effective decisions. In fact, groups may sometimes achieve results beyond what they could have done as individuals. Groups may also make the task more enjoyable for the members. Finally, when the decision is made by a group rather than a single individual, implementation of the decision will be easier, because group members will be more invested in the decision. If the group is diverse, better decisions may be made, because different group members may have different ideas based on their backgrounds and experiences. Research shows that for top management teams, diverse groups that debate issues make decisions that are more comprehensive and better for the bottom line.Simons, T., Pelled, L. H., & Smith, K. A. (1999). Making use of difference: Diversity, debate, decision comprehensiveness in top management teams. Academy of Management Journal, 42, 662–73.

Despite its popularity within organizations, group decision making suffers from a number of disadvantages. We know that groups rarely outperform their best member.Miner, F. C. (1984). Group versus individual decision making: An investigation of performance measures, decision strategies, and process losses/gains. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 33, 112–24. While groups have the potential to arrive at an effective decision, they often suffer from process losses. For example, groups may suffer from coordination problems. Anyone who has worked with a team of individuals on a project can attest to the difficulty of coordinating members’ work or even coordinating everyone’s presence in a team meeting. Furthermore, groups can suffer from groupthink. Finally, group decision making takes more time compared to individual decision making, because all members need to discuss their thoughts regarding different alternatives.

Thus, whether an individual or a group decision is preferable will depend on the specifics of the situation. For example, if there is an emergency and a decision needs to be made quickly, individual decision making might be preferred. Individual decision making may also be appropriate if the individual in question has all the information needed to make the decision and if implementation problems are not expected. On the other hand, if one person does not have all the information and skills needed to make a decision, if implementing the decision will be difficult without the involvement of those who will be affected by the decision, and if time urgency is more modest, then decision making by a group may be more effective.

Figure 8.10 Advantages and Disadvantages of Different Levels of Decision Making

Groupthink

Figure 8.11

In January 1986, the space shuttle Challengerexploded seventy-three seconds after liftoff, killing all seven astronauts aboard. The decision to launch Challenger that day, despite problems with mechanical components of the vehicle and unfavorable weather conditions, is cited as an example of groupthink.Esser, J. K., & Lindoerfer, J. L. (1989). Groupthink and the space shuttle Challengeraccident: Toward a quantitative case analysis. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 2, 167–77; Moorhead, G., Ference, R., & Neck, C. P. (1991). Group decision fiascoes continue: Space shuttle Challenger and a revised groupthink framework. Human Relations, 44, 539–50.

Have you ever been in a decision-making group that you felt was heading in the wrong direction but you didn’t speak up and say so? If so, you have already been a victim of groupthink. Groupthink is a tendency to avoid a critical evaluation of ideas the group favors. Iriving Janis, author of a book called Victims of Groupthink, explained that groupthink is characterized by eight symptoms:Janis, I. L. (1972). Victims of groupthink. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

- Illusion of invulnerability is shared by most or all of the group members, which creates excessive optimism and encourages them to take extreme risks.

- Collective rationalizations occur, in which members downplay negative information or warnings that might cause them to reconsider their assumptions.

- An unquestioned belief in the group’s inherent moralityoccurs, which may incline members to ignore ethical or moral consequences of their actions.

- Stereotyped views of outgroups are seen when groups discount rivals’ abilities to make effective responses.

- Direct pressure is exerted on any members who express strong arguments against any of the group’s stereotypes, illusions, or commitments.

- Self-censorship occurs when members of the group minimize their own doubts and counterarguments.

- Illusions of unanimity occur, based on self-censorship and direct pressure on the group. The lack of dissent is viewed as unanimity.

- The emergence of self-appointed mindguards happens when one or more members protect the group from information that runs counter to the group’s assumptions and course of action.

Recommendations for Avoiding Groupthink

Groups should do the following:

- Discuss the symptoms of groupthink and how to avoid them.

- Assign a rotating devil’s advocate to every meeting.

- Invite experts or qualified colleagues who are not part of the core decision-making group to attend meetings and get reactions from outsiders on a regular basis and share these with the group.

- Encourage a culture of difference where different ideas are valued.

- Debate the ethical implications of the decisions and potential solutions being considered.

Individuals should do the following:

- Monitor personal behavior for signs of groupthink and modify behavior if needed.

- Check for self-censorship.

- Carefully avoid mindguard behaviors.

- Avoid putting pressure on other group members to conform.

- Remind members of the ground rules for avoiding groupthink if they get off track.

Group leaders should do the following:

- Break the group into two subgroups from time to time.

- Have more than one group work on the same problem if time and resources allow it. This makes sense for highly critical decisions.

- Remain impartial and refrain from stating preferences at the outset of decisions.

- Set a tone of encouraging critical evaluations throughout deliberations.

- Create an anonymous feedback channel through which all group members can contribute if desired.

Sources: Adapted and expanded from Janis, I. L. (1972). Victims of groupthink. New York: Houghton Mifflin; Whyte, G. (1991). Decision failures: Why they occur and how to prevent them. Academy of Management Executive, 5, 23–31.

Tools and Techniques for Making Better Decisions

Nominal Group Technique (NGT) was developed to help with group decision making by ensuring that all members participate fully. NGT is not a technique to be used routinely at all meetings. Rather, it is used to structure group meetings when members are grappling with problem solving or idea generation. It follows four steps.Delbecq, A. L., Van de Ven, A. H., & Gustafson, D. H. (1975). Group techniques for program planning: A guide to nominal group and Delphi processes. Glenview, IL: Scott Foresman. First, each member of the group begins by independently and silently writing down ideas. Second, the group goes in order around the room to gather all the ideas that were generated. This process continues until all the ideas are shared. Third, a discussion takes place around each idea, and members ask for and give clarification and make evaluative statements. Finally, group members vote for their favorite ideas by using ranking or rating techniques. Following the four-step NGT helps to ensure that all members participate fully, and it avoids group decision-making problems such as groupthink.

Figure 8.12

Communicating is a key aspect of making decisions in a group. In order to generate potential alternatives, brainstorming and critical thinking are needed to avoid groupthink.

© 2010 Jupiterimages Corporation

Delphi Technique is unique because it is a group process using written responses to a series of questionnaires instead of physically bringing individuals together to make a decision. The first questionnaire asks individuals to respond to a broad question such as stating the problem, outlining objectives, or proposing solutions. Each subsequent questionnaire is built from the information gathered in the previous one. The process ends when the group reaches a consensus. Facilitators can decide whether to keep responses anonymous. This process is often used to generate best practices from experts. For example, Purdue University Professor Michael Campion used this process when he was editor of the research journal Personnel Psychology and wanted to determine the qualities that distinguished a good research article. Using the Delphi technique, he was able to gather responses from hundreds of top researchers from around the world and distill them into a checklist of criteria that he could use to evaluate articles submitted to his journal, all without ever having to leave his office.Campion, M. A. (1993). Article review checklist: A criterion checklist for reviewing research articles in applied psychology. Personnel Psychology, 46, 705–18.

Majority rule refers to a decision-making rule in which each member of the group is given a single vote and the option receiving the greatest number of votes is selected. This technique has remained popular, perhaps due to its simplicity, speed, ease of use, and representational fairness. Research also supports majority rule as an effective decision-making technique.Hastie, R., & Kameda, T. (2005). The robust beauty of majority rules in group decisions. Psychological Review, 112, 494–508. However, those who did not vote in favor of the decision will be less likely to support it.

Consensus is another decision-making rule that groups may use when the goal is to gain support for an idea or plan of action. While consensus tends to require more time, it may make sense when support is needed to enact the plan. The process works by discussing the issues at hand, generating a proposal, calling for consensus, and discussing any concerns. If concerns still exist, the proposal is modified to accommodate them. These steps are repeated until consensus is reached. Thus, this decision-making rule is inclusive, participatory, cooperative, and democratic. Research shows that consensus can lead to better accuracy,Roch, S. G. (2007). Why convene rater teams: An investigation of the benefits of anticipated discussion, consensus, and rater motivation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 104, 14–29. and it helps members feel greater satisfaction with decisions.Mohammed, S., & Ringseis, E. (2001). Cognitive diversity and consensus in group decision making: The role of inputs, processes, and outcomes. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 85, 310–35. However, groups take longer with this approach, and if consensus cannot be reached, members tend to become frustrated.Peterson, R. (1999). Can you have too much of a good thing? The limits of voice for improving satisfaction with leaders. Personality and Social Psychology, 25, 313–24.

Group Decision Support Systems (GDSS) are interactive computer-based systems that are able to combine communication and decision technologies to help groups make better decisions. Research shows that a GDSS can actually improve the output of groups’ collaborative work through higher information sharing.Lam, S. S. K., & Schaubroeck, J. (2000). Improving group decisions by better pooling information: A comparative advantage of group decision support systems. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 565–73. Organizations know that having effective knowledge management systems to share information is important, and their spending reflects this reality. Businesses invested $2.7 billion into new systems in 2002, and projections were for this number to double every five years. As the popularity of these systems grows, they risk becoming counterproductive. Humans can only process so many ideas and information at one time. As virtual meetings grow larger, it is reasonable to assume that information overload can occur and good ideas will fall through the cracks, essentially recreating a problem that the GDSS was intended to solve, which is to make sure every idea is heard. Another problem is the system possibly becoming too complicated. If the systems evolve to a point of uncomfortable complexity, it has recreated the problem. Those who understand the interface will control the narrative of the discussion, while those who are less savvy will only be along for the ride.Nunamaker, J. F., Jr., Dennis, A. R., Valacich, J. S., Vogel, D. R., & George, J. F. (1991, July). Electronic meetings to support group work. Communications of the ACM, 34(7), 40–61.Lastly, many of these programs fail to take into account the factor of human psychology. These systems could make employees more reluctant to share information because of lack of control, lack of immediate feedback, or the fear of online “flames.”

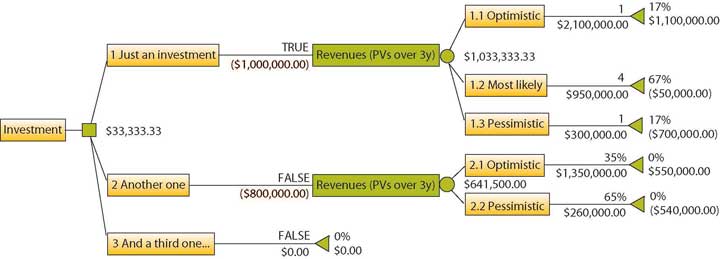

Decision trees are diagrams in which answers to yes or no questions lead decision makers to address additional questions until they reach the end of the tree. Decision trees are helpful in avoiding errors such as framing bias.Wright, G., & Goodwin, P. (2002). Eliminating a framing bias by using simple instructions to “think harder” and respondents with managerial experience: Comment on “breaking the frame.” Strategic Management Journal, 23, 1059–67. Decision trees tend to be helpful in guiding the decision maker to a predetermined alternative and ensuring consistency of decision making—that is, every time certain conditions are present, the decision maker will follow one course of action as opposed to others if the decision is made using a decision tree.

Figure 8.13

Utilizing decision trees can improve investment decisions by optimizing them for maximum payoff. A decision tree consists of three types of nodes. Decision nodes are commonly represented by squares. Chance nodes are represented by circles. End nodes are represented by triangles.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- There are trade-offs between making decisions alone and within a group.

- Groups have a greater diversity of experiences and ideas than individuals, but they also have potential process losses such as groupthink.

- Groupthink can be avoided by recognizing the eight symptoms discussed.

- Finally, there are a variety of tools and techniques available for helping to make more effective decisions in groups, including the nominal group technique, Delphi technique, majority rule, consensus, GDSS, and decision trees.

EXERCISES

- Do you prefer to make decisions in a group or alone? What are the main reasons for your preference?

- Have you been in a group that used the brainstorming technique? Was it an effective tool for coming up with creative ideas? Please share examples.

- Have you been in a group that experienced groupthink? If so, how did you deal with it?

- Which of the decision-making tools discussed in this chapter (NGT, Delphi, and so on) have you used? How effective were they?

8.4 Chapter Summary and Case

CHAPTER SUMMARY

- Decision making is a critical component of business.

- Some decisions are obvious and can be made quickly, without investing much time and effort in the decision-making process. Others, however, require substantial consideration of the circumstances surrounding the decision, available alternatives, and potential outcomes.

- Fortunately, there are several methods that can be used when making a difficult decision, depending on various environmental factors. Some decisions are best made by groups. Group decision-making processes also have multiple models to follow, depending on the situation.

- Even when specific models are followed, groups and individuals can often fall into potential decision-making pitfalls. If too little information is available, decisions might be made based on a feeling. On the other hand, if too much information is presented, people can suffer from analysis paralysis, in which no decision is reached because of the overwhelming number of alternatives.

CHAPTER CASE

Moon Walk and TalkNASA educational materials. Retrieved March 2, 2008, from http://www.nasa.gov/audience/foreducators/topnav/materials/listbytype/Survival_Lesson.html.

Warning: Do not discuss this exercise with other members of your class until instructed to do so.

You are a member of the moon space crew originally scheduled to rendezvous with a mother ship on the lighted surface of the moon. Due to mechanical difficulties, however, your ship was forced to land at a spot some 200 miles (320 km) from the rendezvous point. During reentry and landing, much of the equipment aboard was damaged, and because survival depends on reaching the mother ship, the most critical items available must be chosen for the 200-mile (320 km) trip. Please see the list of the fifteen items left intact and undamaged after landing. Your task is to rank the items in terms of their importance for your crew to reach the rendezvous point. Place the number 1 by the most important, 2 by the next most important, and so on, with 15 being the least important.

TABLE 8.1

| Undamaged items | My ranking | Group ranking | NASA ranking | My difference | Group difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Box of matches | |||||

| Food concentrates | |||||

| 50 feet of nylon | |||||

| Parachute silk | |||||

| Portable heating unit | |||||

| Two 45-caliber pistols | |||||

| One case dehydrated milk | |||||

| Two 100 lb. tanks oxygen | |||||

| Stellar map (of moon’s constellations) | |||||

| Life raft | |||||

| Magnetic compass | |||||

| 5 gallons of water | |||||

| Signal flares | |||||

| First aid kit containing injection needles | |||||

| Solar powered FM receiver–transmitter |